In an unexpected convergence of disparate scientific fields, recent investigations into the microscopic behavior of common foams have revealed a profound mathematical kinship with the intricate processes underpinning modern artificial intelligence. While previously thought to settle into stable, glass-like arrangements, new findings demonstrate that the internal structures of foams are in a perpetual state of flux. Strikingly, the mathematical descriptions governing this ceaseless rearrangement bear a striking resemblance to the optimization techniques employed in deep learning, suggesting a potentially universal principle of self-organization across physical, biological, and computational domains.

Foams are ubiquitous in daily existence, manifesting as the ephemeral lather of soap, the creamy texture of shaving foam, or the airy consistency of culinary emulsions like mayonnaise. For an extended period, the scientific consensus regarding these fascinating materials posited a behavior akin to that of glass: their constituent elements—tiny bubbles suspended in a liquid or solid matrix—were believed to become rigidly locked into disordered but essentially static positions once formed. This perspective lent itself to the macroscopic observation that foams generally maintain their shape and exhibit a certain resilience, bouncing back after deformation, much like a solid. Scientists often utilized foams as accessible model systems to explore the mechanics of other dense, dynamic, and complex materials, including the intricate structures within living cells, due to their ease of creation and observation coupled with their multifaceted mechanical properties.

However, a groundbreaking paradigm shift has emerged from the laboratories of the University of Pennsylvania. Engineers there have meticulously demonstrated that beneath their outwardly stable appearance, the internal architecture of foams is anything but quiescent. Far from settling into fixed configurations, the internal components — the individual bubbles — are engaged in a continuous, dynamic dance of reorganization. This revelation fundamentally challenges the long-held static view and introduces an entirely new lens through which to comprehend these familiar substances.

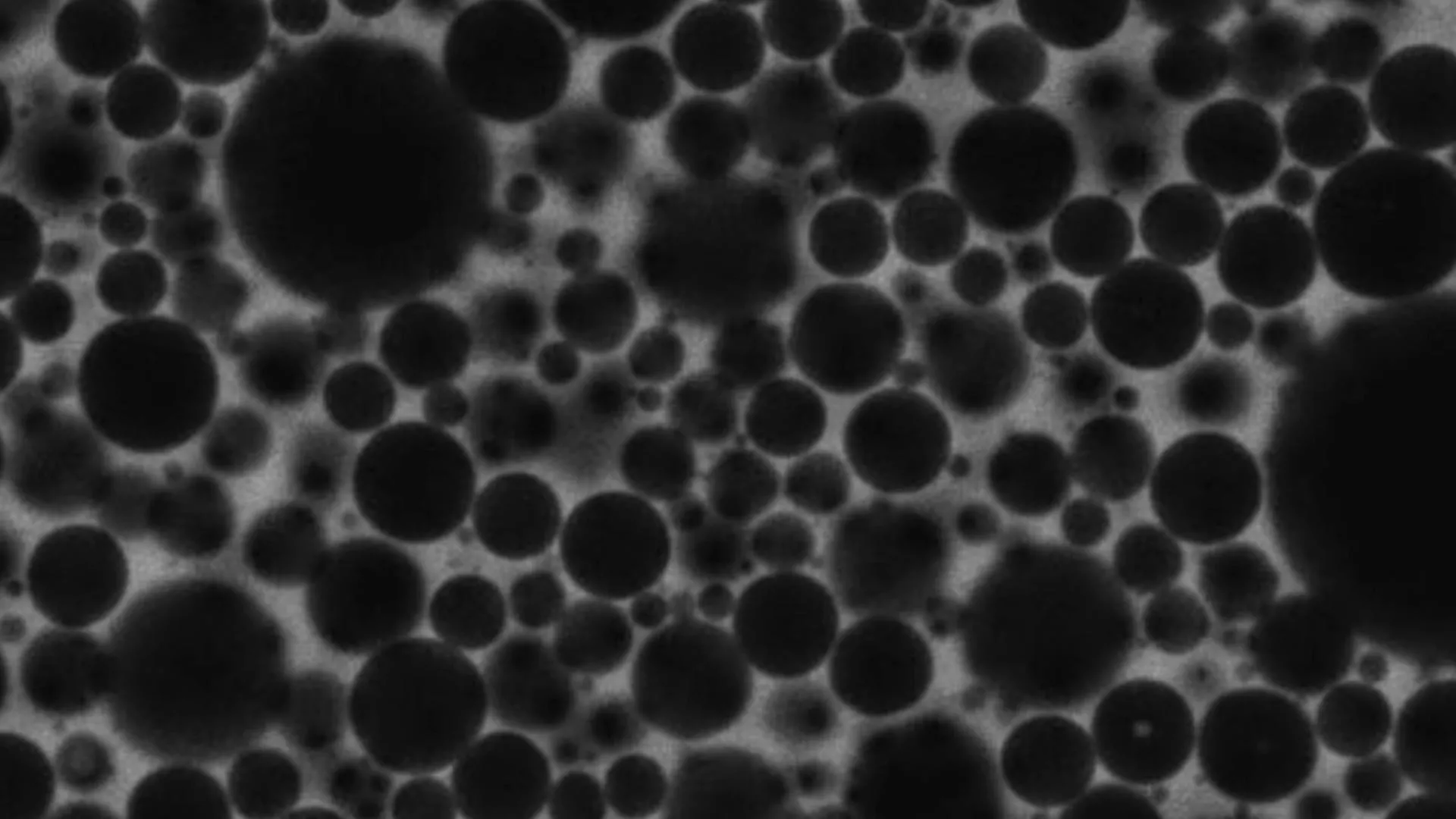

The most compelling aspect of this discovery lies in the unexpected mathematical congruence between this internal foam dynamism and the operational logic of deep learning. Deep learning, the computational engine driving much of contemporary artificial intelligence, operates by continuously adjusting vast numbers of internal parameters during its training phase, gradually refining its understanding and performance. The Penn researchers observed that the complex, wandering trajectories of bubbles within a wet foam, simulated with advanced computational models, did not lead to a final, stationary equilibrium. Instead, these bubbles persistently explored a multitude of possible arrangements, never truly locking into a single, ultimate state.

From a purely mathematical standpoint, this persistent exploration mirrors the iterative adjustment processes central to deep learning. During training, an AI system does not arrive at a singular, definitive set of parameters that represent absolute "knowledge." Rather, it continually refines these parameters, akin to a continuous learning process, rather than concluding in a fixed, immutable state. Professor John C. Crocker, a distinguished figure in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (CBE) and co-senior author of the pivotal study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, underscored this remarkable parallel. He noted the striking similarity between the constant self-reorganization of foams and the mathematical principles governing modern AI systems, posing a profound open question about the underlying reasons for this convergence and its potential to revolutionize our understanding of adaptive materials and biological systems.

The traditional theoretical framework for understanding foam mechanics often invoked an "energy landscape" metaphor. In this conceptual model, individual bubbles were envisioned as particles or "rocks" traversing a terrain of varying energy states. The prevailing assumption was that these bubbles would naturally gravitate towards positions of lower energy, much like a boulder rolling downhill until it reaches a valley floor, where it would then remain. This theoretical construct served to explain the apparent stability of foams once they had formed, suggesting that once the bubbles found their lowest energy configurations, their movement would cease, resulting in a static, settled structure.

Yet, this elegant theoretical model began to diverge from empirical reality. When researchers meticulously analyzed real-world foam data, the observed behavior consistently defied these long-standing predictions. Professor Crocker recounted that the initial signs of this discrepancy surfaced nearly two decades ago. However, at that time, the scientific community lacked the sophisticated mathematical instruments necessary to fully articulate and explain the complex dynamics that were actually occurring within the foams. The traditional physics, while robust for many other systems, proved inadequate for describing a system that perpetually reorganized itself without ever achieving a final, static equilibrium.

The breakthrough in reconciling this "mismatch between theory and reality" arrived with the application of insights derived from the field of artificial intelligence. Modern AI systems, particularly those employing deep learning, learn through an iterative process of adjusting numerical parameters. Early approaches to AI training often aimed to push these systems towards a singular, optimal solution—a "deepest valley" in the metaphorical error landscape—that perfectly corresponded to their training data. This pursuit of absolute precision, however, often led to a phenomenon known as overfitting, where models became overly specialized to the training data and performed poorly when confronted with new, unseen information.

Deep learning fundamentally relies on optimization methodologies closely related to gradient descent, a mathematical technique that guides a system step-by-step towards configurations that progressively minimize error. Over time, AI researchers realized a crucial insight: pushing models into the deepest possible solutions was counterproductive. As Professor Robert Riggleman, also a Professor in CBE and co-senior author of the paper, explained, the key realization was that true generalization—the ability of an AI model to perform effectively on novel data—was achieved not by seeking the absolute lowest point in the error landscape, but by operating within "flatter parts of the landscape," where numerous solutions exhibited similarly high performance. This approach prevents the model from becoming overly rigid and allows for greater adaptability.

It was this refined understanding of AI optimization that provided the missing framework for interpreting the perplexing behavior of foams. When the Penn research team re-examined their foam data through this lens, the striking parallelism became unequivocally clear. Foam bubbles, much like well-trained AI models, do not settle into singular, deep, and unyielding energy minima. Instead, they continually fluctuate and explore within broader regions where a multitude of configurations are equally viable and energetically accessible. This perpetual, exploratory motion within a "flat landscape" of possibilities directly mirrors how modern AI systems operate during their learning phases, eschewing rigid fixation for continuous adaptation. The very mathematical principles that elucidated the effectiveness and generalization capabilities of deep learning also, it turns out, precisely capture the intrinsic behavior of foams that had puzzled scientists for decades.

The implications of these findings extend far beyond the immediate study of foams, raising profound new questions in a field many presumed to be comprehensively understood. This re-evaluation of fundamental material behavior may, in itself, constitute one of the study’s most significant contributions. By demonstrating that foam bubbles are not frozen in glass-like states but instead engage in dynamic processes akin to computational learning algorithms, the research prompts a fundamental rethinking of how other complex systems, both animate and inanimate, might behave and self-organize.

This groundbreaking research opens promising avenues for the development of innovative materials. An understanding of how materials can intrinsically reorganize and adapt to their environments, without external control, could lead to the creation of truly smart, responsive substances capable of sensing and adjusting to changes in their surroundings. Imagine materials that can self-repair, change properties on demand, or even mimic biological functions.

Furthermore, the study holds significant promise for advancing our comprehension of biological systems. Professor Crocker’s team is now revisiting the very system that initially sparked his interest in foams: the cytoskeleton. This intricate, microscopic framework within living cells is crucial for cellular structure, movement, and division. Like foams, the cytoskeleton must constantly reorganize and adapt to maintain cellular function while preserving its overall structural integrity. The discovery of shared mathematical principles between foams and AI learning could provide invaluable new tools and perspectives for deciphering the complex, dynamic mechanics of cellular life.

The deeper philosophical question of why the mathematics of deep learning so accurately characterizes the behavior of foams remains an open and fascinating area for future inquiry. This unexpected interdisciplinary bridge hints at the possibility that these sophisticated mathematical tools, originally conceived for artificial intelligence, may possess a far broader applicability than previously imagined. Their utility could extend across diverse scientific domains, potentially unlocking entirely new lines of investigation into the fundamental organizing principles that govern the universe, from the simplest soap bubble to the most complex neural networks and living organisms. This study represents a compelling testament to the interconnectedness of scientific inquiry, revealing hidden symmetries and universal logics in the most unexpected places.

This research was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science and received support from the National Science Foundation Division of Materials Research. Additional co-authors included Amruthesh Thirumalaiswamy and Clary Rodríguez-Cruz.