A groundbreaking scientific inquiry has unveiled a previously underestimated vulnerability within human physiology, revealing that a significant number of commonly encountered anthropogenic chemicals possess the capacity to disrupt the delicate ecosystem of beneficial microorganisms residing within the human gut. This extensive laboratory investigation identifies a substantial subset of these substances as detrimental agents, capable of impeding or arresting the proliferation of critical bacterial species essential for maintaining holistic bodily functions.

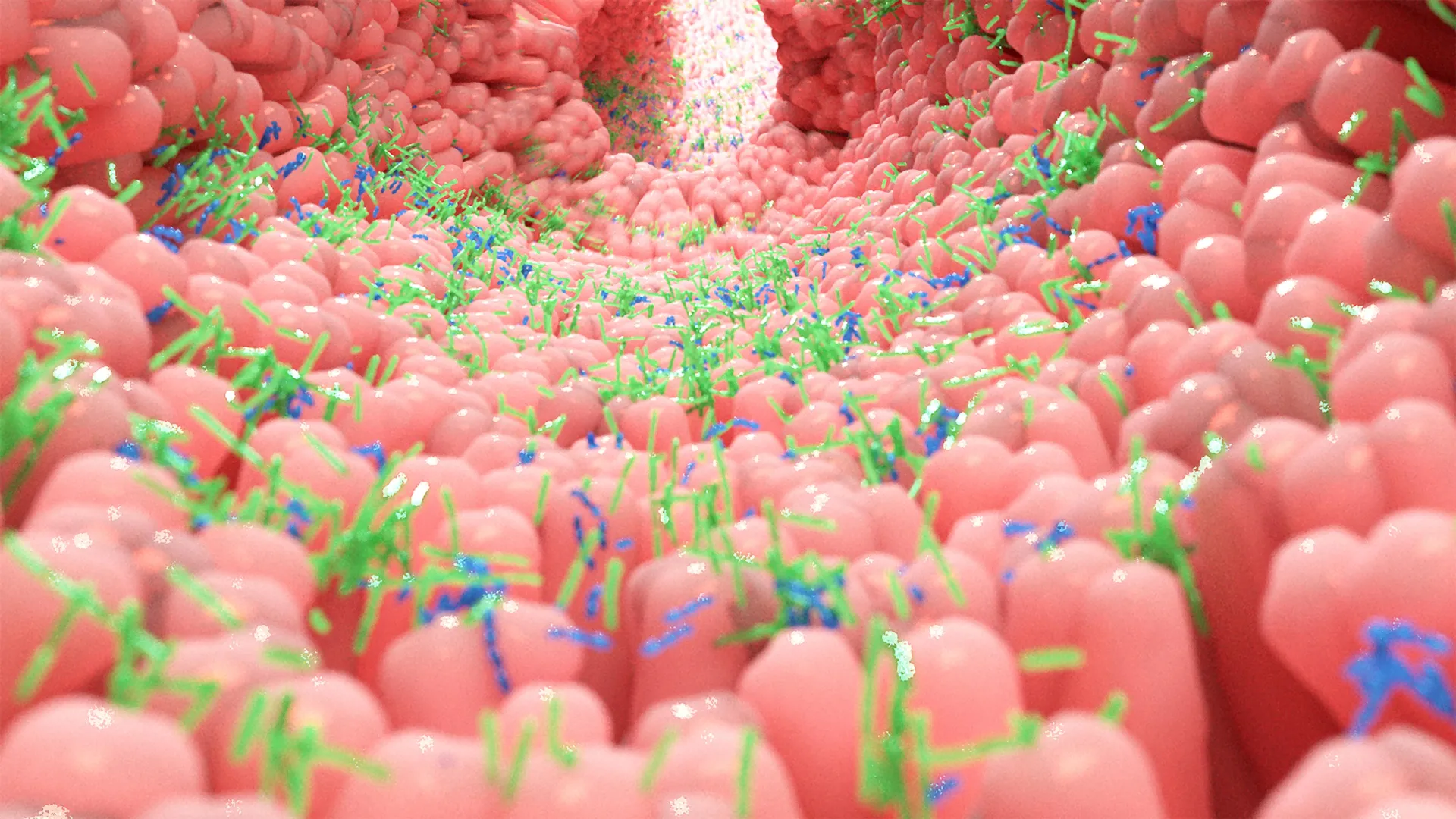

The human gut microbiome represents a complex, dynamic community of trillions of microorganisms, primarily bacteria, which co-evolved with their human hosts to perform a myriad of vital functions. This intricate internal environment contributes fundamentally to nutrient metabolism, immune system maturation, pathogen defense, and even neurobehavioral regulation through the gut-brain axis. Its integrity is paramount for overall well-being, and disturbances, termed dysbiosis, have been increasingly linked to a spectrum of chronic conditions, ranging from metabolic disorders like obesity and type 2 diabetes to inflammatory bowel diseases, autoimmune conditions, and various mental health challenges. The recent findings underscore an emergent concern regarding the potential for widespread environmental and consumer chemicals to compromise this foundational biological system.

A striking aspect of this comprehensive analysis is the identification of numerous compounds that are integral to modern industrial and agricultural practices, and subsequently, pervasive in daily human life. These chemicals infiltrate the human environment through diverse pathways, including the food chain, contaminated water sources, and direct contact with consumer products. Historically, the prevailing assumption in toxicology and risk assessment for many of these substances was a negligible interaction with bacterial life, particularly within the human gastrointestinal tract. This new evidence fundamentally challenges that long-held belief, necessitating a re-evaluation of current chemical safety paradigms. The sheer volume of chemicals implicated, 168 out of 1076 tested, suggests a systemic issue rather than isolated incidents of adverse effects, pointing to a potential blind spot in existing regulatory frameworks.

Beyond direct microbial suppression, the research illuminates a profoundly concerning collateral effect: the induction of antimicrobial resistance. When gut bacteria are subjected to the selective pressures exerted by these chemical contaminants, some species exhibit adaptive responses aimed at survival. This evolutionary adjustment can, in certain circumstances, confer resistance to clinically vital antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin, a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone. The mechanisms underlying such adaptations are multifaceted, potentially involving the upregulation of efflux pumps that expel both the chemical and the antibiotic, alterations in cellular targets, or the acquisition of resistance genes. Should similar adaptive processes occur within the complex milieu of the human gut in vivo, the implications for public health are dire. The effectiveness of current antimicrobial therapies could be further eroded, rendering common bacterial infections increasingly recalcitrant to treatment and exacerbating the already global crisis of antibiotic resistance. This potential synergy between chemical pollution and antibiotic resistance adds another layer of urgency to understanding and mitigating the environmental impact of these ubiquitous substances.

The study, spearheaded by researchers from the University of Cambridge, was executed with rigorous methodological precision. It involved the systematic screening of over a thousand distinct chemical contaminants against a panel of 22 representative species of gut bacteria, all conducted under carefully controlled laboratory conditions. While the human gut microbiome encompasses an estimated 4,500 different bacterial types, the selection of 22 key species provided a robust initial platform to identify broad patterns of toxicity and adaptation. This controlled in vitro environment allowed for the isolation of direct chemical effects on bacterial growth and function, minimizing confounding variables inherent in more complex biological systems. The scale of the investigation, encompassing such a large number of diverse chemicals, represents a significant undertaking in environmental toxicology.

Among the categories of chemicals found to exert deleterious effects on gut bacteria are several classes with widespread applications. Pesticides, a broad group encompassing herbicides and insecticides, are routinely deployed in agricultural settings globally to protect crops from pests and weeds. Residues from these compounds can persist on produce, enter soil and water systems, and subsequently be ingested by humans. Industrial compounds, another major category, include substances like flame retardants, which are incorporated into textiles and electronics to inhibit combustion, and plasticizers, used to enhance the flexibility and durability of plastics. These industrial chemicals are pervasive in consumer products and building materials, leading to chronic low-level human exposure through various routes, including inhalation of dust, dermal absorption, and ingestion. The discovery that these compounds, many of which were not previously considered biologically active in this context, are toxic to critical gut microbes underscores a significant oversight in past hazard assessments.

The revelation that such common chemicals can perturb the gut microbiome highlights a critical deficiency in conventional chemical safety evaluation protocols. Historically, regulatory toxicology has focused on assessing direct toxicity to mammalian cells and organisms, often concentrating on acute effects or specific organ damage. The complex interplay within microbial ecosystems and their profound impact on host health has largely remained outside the purview of standard testing frameworks. Chemicals are typically designed with specific targets in mind—for instance, an insecticide is engineered to target insect physiology, and a herbicide to affect plant growth pathways. The assumption has been that their activity would be highly specific, neglecting the possibility of off-target effects on non-target biological systems, particularly microbial ones, which share fundamental biochemical processes with other life forms. This reductionist approach has evidently overlooked a crucial dimension of chemical safety.

Leveraging the extensive dataset generated from their experiments, the Cambridge researchers developed an innovative machine learning model. This predictive tool is designed to forecast the likelihood of industrial chemicals, both those currently in widespread use and those still under development, causing harm to human gut bacteria. The deployment of artificial intelligence in this context represents a significant leap forward in proactive toxicology. By identifying potential threats at earlier stages of chemical development, this model offers a pathway toward implementing "safe by design" principles, where environmental and health impacts, including those on the microbiome, are considered from the outset. This predictive capability holds immense promise for informing future regulatory decisions and guiding the chemical industry toward more benign alternatives. The full findings and the details of this novel model were formally published in the esteemed journal Nature Microbiology, signifying the scientific community’s recognition of their profound implications.

Experts involved in the research have articulated a clear mandate for a paradigm shift in chemical safety assessment. Dr. Indra Roux, a leading researcher at the University of Cambridge’s MRC Toxicology Unit and the study’s primary author, emphasized the unexpected breadth of effects observed. "Our investigations revealed that numerous chemicals, ostensibly engineered for highly specific actions—such as targeting insects or fungi—exhibit significant adverse interactions with gut bacteria. The potency of these effects was particularly surprising for certain compounds. For instance, many industrial chemicals, including flame retardants and plasticizers, which are prevalent in our daily environment, were not previously thought to exert any significant biological activity on living organisms, yet they demonstrably do." Professor Kiran Patil, senior author of the study, further underscored the transformative potential of the research: "The profound utility of this extensive study resides in the actionable data now available, which empowers us to predict the effects of novel chemical compounds. Our ultimate objective is to usher in an era where new chemicals are inherently safe by design, minimizing unintended biological consequences." Dr. Stephan Kamrad, another key contributor to the work, reiterated the critical imperative: "Future safety assessments for chemicals intended for human use must unequivocally incorporate evaluations of their impact on our gut bacteria, given the undeniable exposure pathways through our food and water systems."

Despite these significant strides, substantial knowledge gaps persist, particularly regarding the precise mechanisms and consequences of real-world chemical exposure on the gut microbiome and, subsequently, on human health. The researchers acknowledge that while gut bacteria are likely to be routinely exposed to many of the chemicals tested, the exact concentrations reaching the digestive system and the cumulative effects of chronic, low-level exposure remain largely undefined. The complexity of human diets, individual lifestyles, genetic predispositions, and the vast diversity of the microbiome itself introduce considerable variability that is challenging to replicate in controlled laboratory settings. Future research efforts will need to transcend in vitro models to encompass sophisticated in vivo studies, potentially involving advanced biomonitoring techniques, longitudinal cohort studies, and the application of multi-omics technologies (e.g., metagenomics, metabolomics) to track chemical exposure dynamics throughout the human body and correlate them with microbiome changes and health outcomes.

Professor Patil articulated the next crucial phase of investigation: "Having successfully identified these interactions within a controlled laboratory environment, the imperative now is to systematically gather more comprehensive real-world chemical exposure data to ascertain whether analogous effects manifest within human biological systems." Until a more complete understanding emerges from such extensive real-world investigations, the researchers advise implementing precautionary measures to minimize exposure. These practical recommendations include diligent washing of fruits and vegetables to reduce pesticide residues and abstaining from the use of synthetic pesticides in home gardening. These steps, while not a panacea for systemic issues, represent actionable strategies for individuals to reduce their immediate chemical burden.

The implications of this research extend far beyond individual health choices, pointing toward a critical need for systemic change. Policymakers, regulatory bodies, and industry stakeholders must acknowledge the newly recognized vulnerability of the gut microbiome and integrate this understanding into future chemical development, risk assessment, and environmental policy. The vision of "safe by design" chemicals, supported by predictive modeling, offers a proactive path forward, moving away from reactive remediation after harm has occurred. This paradigm shift requires interdisciplinary collaboration across toxicology, microbiology, environmental science, and public health to ensure that the innovations of modern chemistry do not inadvertently undermine the fundamental biological systems vital for human and planetary health. The quiet damage identified within the gut microbiome signals a profound call to action for a more holistic and ecologically informed approach to chemical stewardship.