The silent, unseen depths of the ocean are revealing a disquieting mystery: a critical species known colloquially as the "zombie worm," or formally Osedax, appears to be absent from key deep-sea locations, a phenomenon that has scientists deeply concerned. This perplexing disappearance is not merely an isolated ecological anomaly but signals potentially profound disturbances within fragile deep-sea ecosystems, raising alarms about widespread species loss and the accelerating impacts of long-term climate change on marine environments. The implications extend far beyond these peculiar bone-eating worms, pointing to a weakening of fundamental oceanic processes that underpin biodiversity and nutrient cycling across vast underwater landscapes.

At the heart of this alarming discovery lies a meticulously executed, decade-long deep-sea experiment conducted off the coast of British Columbia. Dr. Fabio De Leo, a senior staff scientist with Ocean Networks Canada (ONC) and an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Victoria’s (UVic) Department of Biology, co-led this ambitious undertaking. The research involved strategically placing whale bones—specifically, the skeletal remains of humpback whales—on the abyssal plain, nearly a thousand meters below the Pacific Ocean’s surface in Barkley Canyon. The objective was to observe the natural colonization and decomposition processes, particularly focusing on the role of specialized organisms like Osedax in these unique deep-sea habitats. Despite years of continuous monitoring, utilizing advanced underwater camera systems, researchers observed a stark and unexpected reality: no trace of the bone-devouring worms was found, challenging established ecological models and signaling a significant environmental shift.

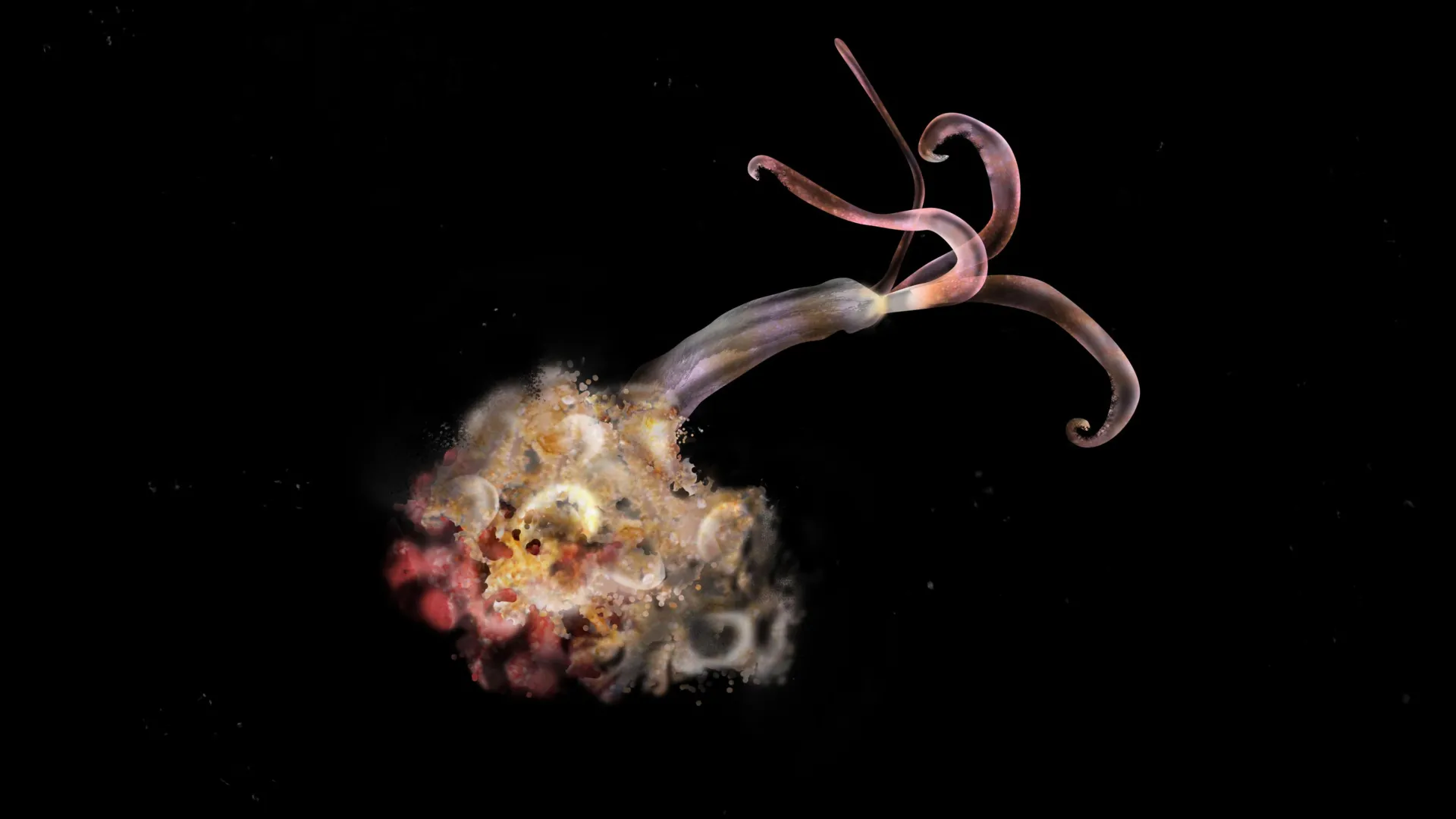

Osedax worms, often referred to as "zombie worms" due to their macabre feeding habits, are extraordinary invertebrates uniquely adapted to life in the deep ocean. These organisms possess a highly specialized biology, notably lacking a conventional mouth, anus, or digestive tract. Instead, they employ a fascinating strategy for nutrient acquisition: they bore intricate, root-like structures directly into the bones of deceased whales. Within these internal "roots" reside a symbiotic community of microbes. These chemosynthetic bacteria perform the crucial function of extracting lipids and proteins from the bone material, converting them into nutrients that subsequently nourish the host worm. This remarkable symbiotic relationship allows Osedax to thrive in an environment where other food sources are scarce and plays an indispensable role in the recycling of organic matter locked within large vertebrate carcasses. Consequently, Osedax are recognized as vital "ecosystem engineers," fundamentally altering their environment to create new niches and facilitate the ecological succession that supports a rich diversity of other deep-sea fauna.

The scientific community often seeks definitive "positive" findings to confirm hypotheses. However, in this case, the absence of Osedax colonization, termed a "negative result," carries immense scientific weight. Over more than ten years of high-resolution underwater camera footage streamed from ONC’s cabled observatory network, the consistent failure to detect Osedax was not merely an inconclusive outcome but a powerful observation indicating a significant departure from expected ecological patterns. Dr. De Leo emphasized the profound nature of this sustained non-observation in such a prolonged experiment. The prevailing scientific hypothesis emerging from this striking absence points towards an insidious environmental factor: unusually low oxygen levels prevalent at the study site, a condition known as hypoxia.

The chosen research site in Barkley Canyon is not arbitrary; it lies within a naturally occurring oxygen minimum zone (OMZ). These zones are regions in the ocean where oxygen concentrations are significantly depleted, often to levels that stress or exclude most aerobic marine life. Barkley Canyon also happens to be situated along the vital migration routes traversed by both humpback and grey whales. When these magnificent marine mammals succumb to natural causes, or tragically, to anthropogenic threats such as ship strikes or entanglement in fishing gear, their colossal bodies descend to the seafloor, creating what scientists term "whale falls." These events are profound ecological occurrences, representing sudden, massive infusions of organic matter into the nutrient-poor deep sea. Whale falls typically support a burst of localized biodiversity, acting as temporary oases for a specialized community of scavengers and decomposers, including Osedax.

However, the persistent lack of Osedax at Barkley Canyon strongly suggests that the expanding and intensifying OMZs in the northeast Pacific and globally are severely disrupting these critical deep-sea ecosystems. Ocean deoxygenation, the process of oxygen loss in marine environments, is a direct consequence of climate change. Warmer waters hold less dissolved oxygen, and increased stratification reduces the mixing of oxygenated surface waters with deeper layers. Furthermore, enhanced nutrient runoff from land can fuel algal blooms, whose decomposition by microbes consumes vast amounts of oxygen, exacerbating hypoxia. The findings from Barkley Canyon are not isolated; preliminary data from ongoing whale fall research near another ONC NEPTUNE observatory site provides further indications of similar concerns elsewhere, suggesting a regional, if not global, pattern of ecological stress.

The ecological importance of the "bone devourer" cannot be overstated. Its disappearance triggers a cascade of detrimental effects throughout the deep-sea food web. Without Osedax to initiate the breakdown of whale bones and facilitate the subsequent stages of ecological succession, the availability of nutrients locked within these substantial organic deposits becomes severely restricted for other organisms. Dr. De Leo likens whale falls to "islands" in the vast deep-sea expanse, serving as "stepping-stone habitats" crucial for the survival and dispersal of Osedax and many other specialist species that rely on these ephemeral food sources. These "islands" are not merely isolated patches; they are interconnected nodes in a broader ecological network, essential for maintaining genetic flow and regional biodiversity.

The profound implications of this research extend to the very real prospect of species loss. Adult Osedax worms are sessile, anchoring themselves to whale bones. However, their larvae are planktonic, capable of drifting vast distances through ocean currents to colonize new whale fall sites, sometimes hundreds of kilometers away. This larval dispersal mechanism is critical for maintaining robust, interconnected populations across wide geographic areas. If the "stepping-stone habitats" provided by whale falls become non-functional due to deoxygenation and the absence of key decomposers like Osedax, the crucial connectivity between these sites will break down. Over extended periods, this fragmentation could lead to significant declines in the diversity of Osedax species, and potentially even their regional extinction, with unknown but likely severe repercussions for the deep-sea ecosystems they help sustain. The loss of these unique specialists represents not only a reduction in biodiversity but also a compromise of fundamental ecological services, such as efficient nutrient recycling in an otherwise energy-limited environment.

The research team also observed troubling signs impacting other deep-sea ecosystem engineers. Xylophaga bivalves, commonly known as wood-boring clams, play an analogous role to Osedax by breaking down submerged wood samples, which also constitute important "fall" ecosystems in the deep sea. While Xylophaga were present on wood samples deployed in Barkley Canyon, their colonization rates were drastically lower compared to observations in oxygen-rich waters. This reduced colonization efficiency has cascading effects. Slower decomposition rates of wood would impede carbon cycling and significantly reduce the formation of intricate burrow habitats, which typically provide shelter and microenvironments for numerous other species. Dr. Craig Smith, professor emeritus from the University of Hawaii and co-leader of the experiment, underscored the gravity of these findings, stating, "It looks like the OMZ expansion, which is a consequence of ocean warming, will be bad news for these amazing whale-fall and wood-fall ecosystems along the northeast Pacific Margin." His expert analysis reinforces the systemic threat posed by climate-driven ocean deoxygenation to multiple deep-sea ecological processes.

The rigorous data collection underpinning these critical observations was made possible by advanced oceanographic infrastructure. Dr. De Leo and Dr. Smith leveraged the capabilities of ONC’s NEPTUNE observatory, specifically its Barkley Canyon Mid-East video camera platform. This cabled observatory provides continuous, real-time access to the deep sea, allowing for sustained observation and the collection of high-definition video footage. Complementing the visual data, oceanographic sensors continuously monitored environmental parameters, while remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) facilitated the deployment and maintenance of experimental setups. This integrated approach, combining long-term fixed observatories with mobile robotic platforms, represents the cutting edge of deep-sea research. Further insights are anticipated in the coming months as researchers continue to monitor a whale fall currently being studied at NEPTUNE’s Clayoquot Slope site, providing additional comparative data and potentially revealing broader patterns of ecological response to environmental stressors.

This pivotal research received essential funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation Major Science Initiative Fund and partially from a US National Science Foundation grant, highlighting its international scientific significance. Moreover, the study directly aligns with United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14, "Life Below Water," which emphasizes the urgent need to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources. The disappearance of Osedax serves as a potent, if cryptic, indicator of the profound and often unseen ecological transformations occurring in the deep ocean. It underscores the critical necessity for sustained scientific inquiry and proactive conservation strategies to mitigate the impacts of anthropogenic climate change on these vital, yet vulnerable, underwater realms, whose health is intrinsically linked to the overall well-being of our planet. The deep sea, once considered remote and immutable, is increasingly revealing its susceptibility to global environmental shifts, demanding immediate attention and concerted action.