A groundbreaking scientific endeavor has, for the first time, successfully isolated and analyzed metabolism-related biomolecules from the fossilized remains of animals that roamed Earth between 1.3 and 3 million years ago. This unprecedented achievement offers an intimate glimpse into the physiological states of these ancient creatures and, by extension, the intricate ecological systems they inhabited, providing insights previously deemed unattainable through conventional paleontological methods.

The pioneering research, spearheaded by an international consortium of scientists, leveraged sophisticated analytical techniques to detect and interpret metabolic signatures preserved within bone. These chemical markers, intrinsically linked to an organism’s health, diet, and physiological responses, enabled a meticulous reconstruction of paleo-climatic and paleo-environmental conditions. The findings, detailed in the esteemed journal Nature, delineate a prehistoric landscape markedly warmer and more humid than the contemporary environments of the same geographical regions, offering critical data for understanding long-term climate dynamics.

The Untapped Potential of Metabolomics in Paleontology

Metabolomics, the systematic study of metabolites—the myriad small molecules produced during metabolic processes such as digestion, energy conversion, and cellular signaling—has revolutionized modern biomedical research. By profiling these compounds, scientists can discern indicators of disease, nutritional status, and environmental exposures in living organisms with remarkable precision. Its application to ancient biological specimens, however, has been profoundly limited, largely due to the pervasive belief that such delicate molecules could not endure the immense geological timescales required for fossilization. Historically, investigations into ancient life forms predominantly relied on genetics (DNA analysis) to establish phylogenetic relationships, offering limited resolution into the day-to-day biological realities of extinct species.

Professor Timothy Bromage, a distinguished figure in molecular pathobiology at NYU College of Dentistry and an affiliated professor in NYU’s Department of Anthropology, led the research team. His long-standing interest in metabolic processes, particularly within bone tissue, prompted the crucial question: could metabolomics extend its analytical power to fossilized remains, thereby illuminating early life forms? The revelation that bone, even after millions of years of fossilization, acts as a repository for metabolites profoundly reshapes our understanding of biomolecular preservation.

The Enigma of Bone Preservation: Beyond Collagen

The scientific community has, in recent decades, acknowledged the remarkable durability of collagen, the fibrous protein fundamental to the structural integrity of bones, skin, and connective tissues. Its detection in ancient specimens, including dinosaur fossils, challenged prior assumptions about the complete degradation of organic matter over vast geological periods. This discovery served as a critical precursor to Bromage’s hypothesis. He reasoned that if collagen, a complex protein, could persist, then other biomolecules might also find sanctuary within the protective microenvironment of bone.

Bone is not merely a rigid structural element; it is a dynamic, porous tissue permeated by an intricate network of microscopic blood vessels. These vascular channels facilitate the continuous exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products with the bloodstream. Bromage theorized that during the osteogenesis (bone formation) and remodeling processes, metabolites circulating in the blood could become physically trapped within the minute, microscopic spaces and lacunae that characterize bone microstructure. Once sequestered within this mineralized matrix, these molecules could potentially be shielded from the hydrolytic degradation, microbial attack, and environmental oxidation that typically obliterate organic compounds over millions of years. This proposed "entrapment mechanism" provides a compelling explanation for their long-term survival.

To rigorously test this innovative hypothesis, the research team employed mass spectrometry, an advanced analytical technique capable of ionizing molecules and separating them based on their mass-to-charge ratio, thereby enabling their precise identification and quantification. Initial validation experiments conducted on contemporary mouse bones yielded an astonishing discovery: nearly 2,200 distinct metabolites were identified. Crucially, the same methodology also confirmed the presence of collagen proteins in these modern bone samples, reinforcing the technique’s efficacy.

Probing the Cradle of Humanity: Early Hominin Landscapes

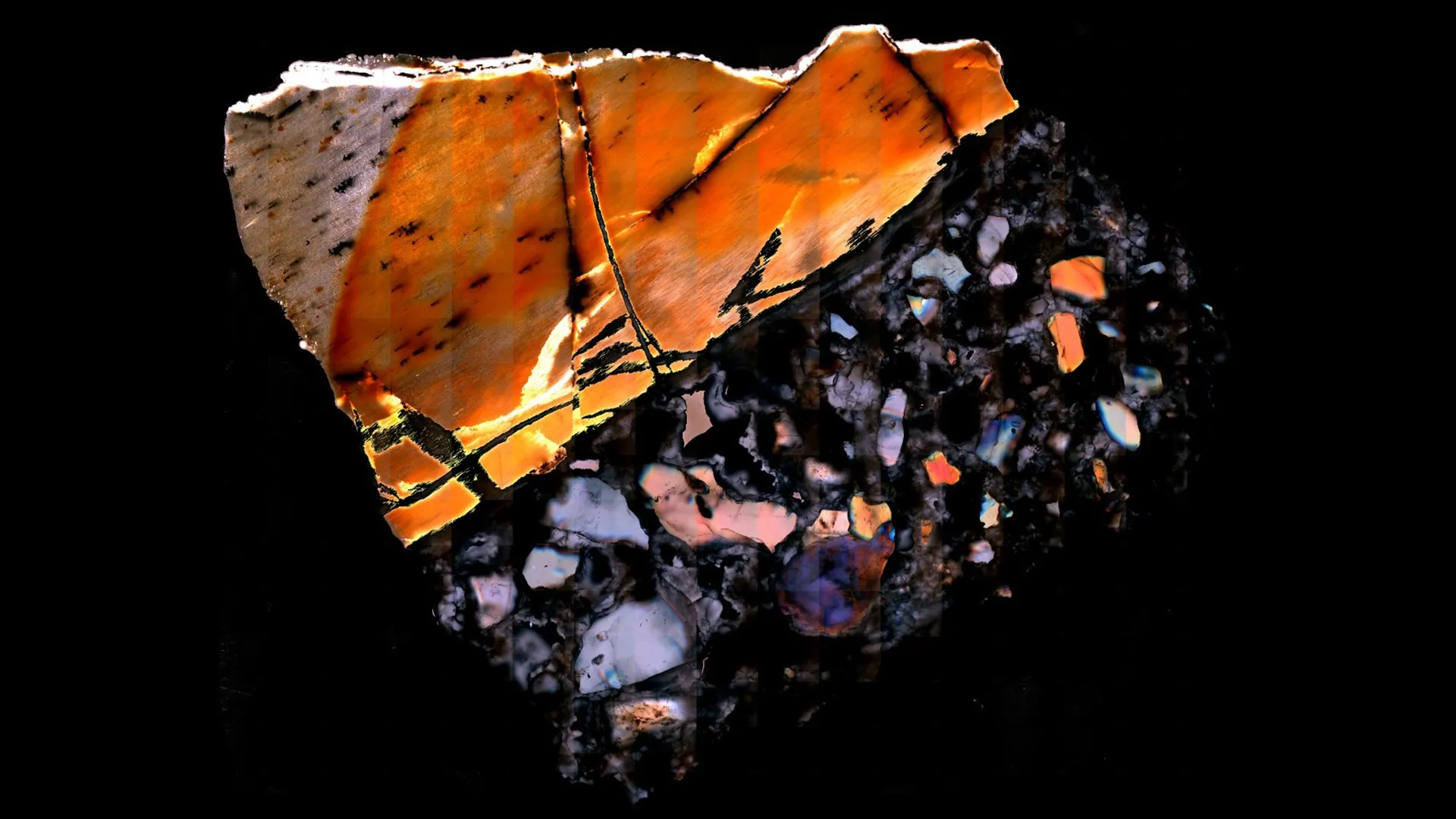

With the methodology validated, the scientists turned their attention to ancient specimens. They applied their novel analytical approach to fossilized animal bones spanning a chronological range of 1.3 million to 3 million years ago. These invaluable samples were sourced from historical paleontological excavations in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa—regions renowned for their rich fossil records pertinent to early human evolution and the study of early hominins.

The chosen fossils represented a diverse array of animals whose modern descendants continue to inhabit these African landscapes. The analyzed collection included bones from various rodents (mice, ground squirrels, gerbils) as well as larger mammals such as an antelope, a pig, and an elephant. The mass spectrometry analysis of these ancient bones successfully identified thousands of metabolites, a significant proportion of which exhibited remarkable congruence with the metabolic profiles observed in their living counterparts, underscoring the fidelity of the preservation and detection process.

A Biomedical Narrative Etched in Bone: Health, Diet, and Disease

The metabolic profiles extracted from these ancient bones offered an unprecedented level of biological detail. Many of the detected metabolites reflected fundamental biological processes, such as the catabolism of amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals—providing direct evidence of the physiological machinery operating within these extinct animals. More remarkably, certain chemical markers were definitively linked to estrogen-related genes, allowing researchers to unequivocally identify the sex of specific fossilized individuals as female. This capacity to determine sex from molecular data in such ancient samples opens new avenues for paleo-demographic studies.

Beyond general physiology, the molecular evidence revealed startling insights into the health status of these prehistoric animals. In one particularly compelling instance, a ground squirrel bone recovered from the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, dated to approximately 1.8 million years ago, bore the unmistakable metabolic signature of a parasitic infection. The identified markers were consistent with an infection by Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of African sleeping sickness in humans, a disease transmitted by tsetse flies.

Professor Bromage elaborated on this discovery: "We identified a metabolite within the squirrel’s bone that is uniquely characteristic of the parasite’s biology, a compound it releases into its host’s bloodstream. Concomitantly, we observed the squirrel’s metabolomic anti-inflammatory response, indicating its physiological battle against the parasitic invasion." This finding represents a monumental step in paleo-pathology, offering direct molecular evidence of ancient disease ecology and host-pathogen interactions.

Environmental Forensics: Reconstructing Ancient Ecosystems

The chemical insights extended beyond individual animal physiology to encompass their dietary habits and the broader ecological context. The analyses successfully identified specific plant compounds within the animal’s metabolic profiles, thereby revealing their dietary composition. While comprehensive plant metabolite databases are less developed than those for animals, the researchers were able to pinpoint compounds indicative of regional flora, such as aloe and asparagus.

Bromage articulated the profound implications: "In the case of the squirrel, its consumption of aloe left a discernible metabolic trace in its bone. Given the highly specific environmental prerequisites for aloe—its temperature, rainfall, and soil conditions—we can now reconstruct the squirrel’s immediate habitat with unprecedented fidelity, including aspects of the tree canopy. This allows us to construct a detailed narrative around each individual animal, painting a vivid picture of its lost world."

These metabolomics-derived environmental reconstructions demonstrate striking concordance with independent geological and ecological research. For example, previous studies have characterized the Olduvai Gorge Bed I in Tanzania as a freshwater woodland and grassland environment, transitioning to drier woodlands and marshy areas in the Upper Bed. Across all studied locations in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, the fossilized metabolic evidence consistently points to paleoclimates that were significantly wetter and warmer than those observed in these regions today. This convergence of evidence strengthens the validity of the metabolomic approach for paleo-environmental reconstruction.

Future Horizons: A New Era in Paleo-Ecological Research

The implications of this breakthrough are far-reaching. The ability to analyze metabolic signatures from ancient fossils inaugurates a new era in paleo-ecological research, offering a level of detail previously unimaginable. It transforms the study of prehistoric environments from broad geological inferences to specific ecological snapshots, akin to contemporary field ecology. This approach can inform our understanding of how past ecosystems responded to climate shifts, providing crucial context for predicting future environmental changes.

Future research trajectories will undoubtedly involve expanding the scope of investigation to a wider array of species, geological periods, and geographical regions. The development of more comprehensive ancient metabolome databases will further enhance the precision of environmental and physiological reconstructions. Moreover, the integration of this metabolomic approach with other ‘omics’ techniques—such as proteomics (study of proteins), lipidomics (study of lipids), and advanced ancient DNA sequencing—promises to yield an even more holistic and granular understanding of ancient life. This multi-modal analytical framework could provide unprecedented insights into evolutionary biology, adaptation, and the complex interplay between organisms and their changing environments over deep time. This scientific leap represents a profound recalibration of what is achievable in the study of our planet’s ancient past.