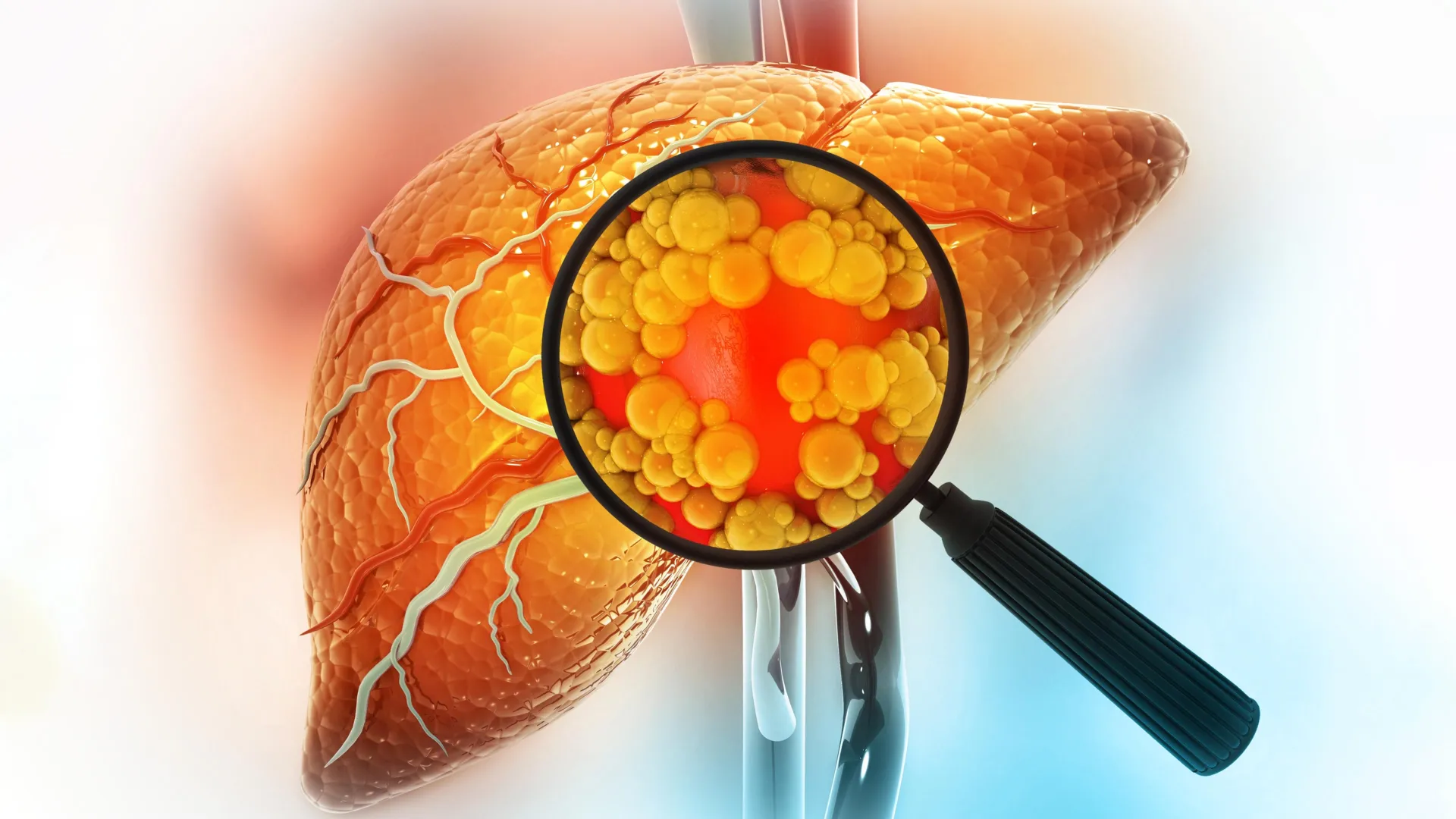

A significant scientific breakthrough originating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has meticulously elucidated a perilous molecular mechanism by which diets rich in fat drastically elevate the susceptibility to liver cancer. This seminal research demonstrates that sustained exposure to high-fat nutrition instigates a profound and dangerous transformation within liver cells, compelling them to revert to an immature, stem-cell-like state that dramatically enhances their vulnerability to oncogenesis. This cellular reprogramming, a survival strategy against metabolic stress, inadvertently lays a groundwork for accelerated tumor formation, offering a critical new perspective on the nexus between diet, cellular plasticity, and carcinogenesis.

Liver cancer, a global health concern with rising incidence, is intricately linked to lifestyle factors, particularly dietary habits. While the association between high-fat diets and liver disease has been well-established, the precise molecular events that bridge this dietary intake to cancer initiation have remained less clear. This new study from MIT, published in the esteemed journal Cell, offers an unprecedented look into these cellular dynamics, revealing how mature liver cells, known as hepatocytes, sacrifice their specialized identity in a desperate attempt to cope with chronic metabolic stress, only to become more susceptible to malignant change.

The core finding revolves around cellular de-differentiation, a process where specialized cells lose their distinct characteristics and adopt a more primitive, stem-cell-like phenotype. The research team observed that repeated exposure of the liver to a high-fat diet acts as a potent environmental stressor, triggering this cellular metamorphosis in hepatocytes. Instead of maintaining their highly specialized functions – critical for metabolism, detoxification, and protein synthesis – these cells undergo a fundamental shift. This transformation, while initially serving as a protective mechanism to withstand the toxic environment induced by excessive fat accumulation and inflammation, paradoxically creates a fertile ground for cancer to take root. As Dr. Alex K. Shalek, a senior author of the study and a prominent figure at MIT’s Institute for Medical Engineering and Sciences, emphasized, cells under chronic duress will prioritize survival, even if it means incurring a long-term risk of tumorigenesis. This intricate trade-off highlights the complex interplay between cellular resilience and disease progression.

To meticulously unravel these molecular events, the researchers employed advanced single-cell RNA sequencing technology. This cutting-edge methodology allowed them to analyze gene activity in individual liver cells at various stages of disease progression in mouse models fed a high-fat diet. Unlike traditional bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across millions of cells, single-cell analysis provides an unparalleled resolution, enabling scientists to track the precise genetic changes occurring within specific cell populations as the liver transitioned from inflammation to scarring and, ultimately, to cancer. This granular view was crucial for identifying the subtle, yet profound, shifts in cellular identity and function that precede malignant transformation.

The detailed molecular analysis revealed a striking pattern of gene expression changes. Early in the exposure to a high-fat diet, hepatocytes began activating a suite of genes associated with cellular survival and stress response. These included genes that actively suppress programmed cell death (apoptosis) and promote sustained cell growth, effectively enabling the cells to endure the harsh, fat-laden environment. Concurrently, genes vital for the normal, specialized functions of the liver, such as those involved in lipid metabolism, glucose regulation, and protein secretion, were progressively down-regulated and eventually silenced. This reciprocal genetic reprogramming represents a critical pivot point: the cells were effectively abandoning their collective tissue responsibilities in favor of individual survival. As Constantine Tzouanas, a co-first author of the paper, eloquently described it, this phenomenon appears to be a stark "trade-off," where the immediate survival of individual cells in a hostile environment takes precedence over the long-term functional integrity of the tissue.

The study further identified several key transcription factors – proteins that regulate gene expression – that appear to orchestrate this dangerous cellular shift. Among these, SOX4 emerged as a particularly intriguing target. SOX4 is typically active during embryonic development, guiding cell differentiation and tissue formation, and is largely silent in mature adult tissues, including a healthy liver. Its re-activation in adult liver cells under high-fat dietary stress is therefore a potent indicator of cellular reversion to an immature state. The presence of such embryonic-like transcription factors in adult tissues is often associated with increased plasticity and, unfortunately, a higher propensity for cancerous transformation.

Beyond SOX4, the research also shed light on other potential therapeutic targets. The thyroid hormone receptor, for instance, was implicated in regulating this cellular state. Notably, a drug targeting this receptor recently received approval for treating a severe form of steatotic liver disease known as MASH fibrosis, underscoring the translational relevance of these findings. Similarly, another enzyme identified in the study, HMGCS2, is already the focus of clinical trials for steatotic liver disease. These discoveries highlight pathways that are not only mechanistically important but also potentially actionable through existing or emerging pharmaceutical interventions.

The clinical implications of these findings are substantial, especially given the global epidemic of steatotic liver disease (SLD), often referred to as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). SLD is a rapidly growing public health crisis, intimately linked to metabolic syndrome, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and, critically, high-fat diets. This condition can progress from simple fat accumulation in the liver to inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ultimately hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of liver cancer. The MIT study provides a profound molecular explanation for this progression, demonstrating that the very cellular mechanisms intended to protect the liver from dietary insult can, over time, predispose it to cancer.

A critical aspect of the research involved validating these mouse model findings in human subjects. The team analyzed liver tissue samples from patients at various stages of liver disease, including those who had not yet developed cancer. The human data remarkably mirrored the observations in mice: a decline in genes essential for normal liver function and a concomitant increase in genes characteristic of immature cell states. Furthermore, these specific gene expression patterns were found to be predictive of patient survival outcomes. Patients exhibiting higher expression of these pro-survival, de-differentiated genes, and lower expression of normal liver function genes, demonstrated reduced survival times following tumor development. This human validation underscores the direct applicability and clinical significance of the mechanistic insights gleaned from the animal studies.

The concept of "why immature liver cells fuel cancer development" is central to understanding the dangerous head start identified by the research. When liver cells revert to a less mature state, they effectively "turn on" many of the same genetic programs that are necessary for cancerous growth. They shed their specialized identity, which would normally constrain their proliferative capacity, and adopt a more plastic, rapidly dividing phenotype. Should a damaging mutation occur in such a primed cell, it is already equipped with the machinery for uncontrolled proliferation and resistance to normal cellular checks. This pre-conditioning allows the mutated cell to bypass several initial hurdles of oncogenesis, accelerating its progression into a full-blown tumor. As Tzouanas noted, these cells are "already off to the races" once they acquire the critical genetic error.

While mice developed liver cancer within approximately a year under a high-fat diet, the researchers estimate that the same pathological trajectory in humans unfolds over a significantly longer period, potentially spanning two decades. This extended timeline offers a crucial window for intervention. The exact pace of progression in humans can be influenced by a multitude of factors, including the specific dietary composition, genetic predispositions, and co-existing risk factors such as chronic alcohol consumption or viral hepatitis, all of which can independently or synergistically push liver cells towards this vulnerable, immature state.

Looking ahead, the research team is focused on exploring the reversibility of these diet-induced cellular changes. A key question is whether adopting a healthier diet, or employing pharmaceutical interventions like GLP-1 agonists (a class of drugs increasingly used for weight management and diabetes), can restore normal liver cell behavior and prevent or even reverse the progression towards malignancy. If these cellular transformations can indeed be undone, it would open new avenues for preventive and therapeutic strategies, offering hope to millions at risk. Furthermore, continued investigation into the identified transcription factors aims to determine their efficacy as precise drug targets, designed to halt the progression from damaged liver tissue to aggressive cancer.

This groundbreaking MIT study not only provides a profound molecular understanding of how high-fat diets contribute to liver cancer but also illuminates novel pathways for intervention. By identifying the critical cellular reprogramming events and the key molecular players involved, the research team has laid a robust foundation for developing targeted therapies and enhancing preventive strategies. The implications extend beyond diet-induced liver cancer, offering insights into the broader mechanisms of cellular plasticity in disease and the intricate dance between environmental stressors and genomic vulnerability, ultimately paving the way for improved patient outcomes in the global fight against cancer.