The nascent field of quantum technology is currently undergoing a profound metamorphosis, transitioning decisively from the realm of fundamental scientific inquiry into a phase of concerted engineering development and practical application. This critical juncture, meticulously analyzed in a recent scholarly publication, draws compelling parallels to the formative period of classical computing, specifically the pivotal era preceding the advent of the transistor—a breakthrough that irrevocably reshaped the landscape of modern technology and global civilization.

This comprehensive assessment, published in a leading scientific journal, synthesizes insights from a collaborative team of distinguished researchers representing prominent institutions including the University of Chicago, Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Innsbruck in Austria, and the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. The study meticulously dissects the contemporary state of quantum information hardware, systematically identifying both the substantial opportunities and the formidable obstacles that lie on the path to realizing scalable quantum computers, robust communication networks, and highly sensitive sensing systems. The consensus articulated within the paper underscores that while foundational principles are now firmly established and functional prototypes exist, the ensuing decade will necessitate an unprecedented degree of collaborative effort and strategic investment to unlock the technology’s full, utility-scale potential.

An Epochal Transition: Echoes of the Transistor’s Dawn

The analogy to the "transistor moment" is particularly salient, capturing the profound significance of the current trajectory. Before the invention of the transistor in 1947, electronic computers were colossal, power-hungry machines built with vacuum tubes. These devices were expensive, unreliable, and limited in scale, primarily confined to government and academic laboratories for specialized calculations. The transistor, a solid-state semiconductor device, revolutionized electronics by enabling miniaturization, reducing power consumption, enhancing reliability, and drastically lowering costs. This innovation paved the way for integrated circuits, microprocessors, personal computers, and eventually, the ubiquitous digital ecosystem we inhabit today.

Similarly, quantum technologies have, for decades, been largely confined to highly specialized laboratory environments, demonstrating proof-of-concept experiments under exquisitely controlled conditions. These early demonstrations, while groundbreaking, were often fragile, susceptible to environmental noise, and difficult to scale beyond a handful of quantum bits (qubits). The current period signifies a departure from this purely experimental phase. Researchers are now grappling with the engineering challenges of building stable, scalable, and error-resistant quantum systems that can perform increasingly complex tasks outside the most pristine lab settings. This shift demands a different mindset, moving from demonstrating "if" quantum effects can be harnessed to figuring out "how" they can be engineered into practical, reliable devices.

David Awschalom, a lead author on the paper and the Liew Family Professor of Molecular Engineering and Physics at the University of Chicago, as well as director of the Chicago Quantum Exchange and the Chicago Quantum Institute, articulated this pivotal shift. He remarked, "This transformative moment in quantum technology is reminiscent of the transistor’s earliest days. The foundational physics concepts are established, functional systems exist, and now we must nurture the partnerships and coordinated efforts necessary to achieve the technology’s full, utility-scale potential. How will we meet the challenges of scaling and modular quantum architectures?" His statement highlights the transition from fundamental scientific discovery to the intricate engineering and systemic integration required for widespread utility.

From Abstract Concepts to Tangible Prototypes: A Decade of Accelerated Progress

The past ten years have witnessed an astonishing acceleration in quantum technology’s maturation. What were once theoretical constructs or delicate laboratory curiosities have evolved into robust systems capable of supporting preliminary applications across various domains, including secure communication, ultra-precise sensing, and novel computational paradigms. This rapid advancement is not accidental; it is largely attributable to the deliberate cultivation of a synergistic ecosystem involving academic institutions, governmental funding agencies, and burgeoning industrial enterprises. This multi-stakeholder collaboration mirrors the successful model that propelled the microelectronics revolution of the mid-20th century, demonstrating that significant technological leaps often necessitate a unified approach transcending traditional institutional boundaries.

Government initiatives, such as the U.S. National Quantum Initiative Act, the European Quantum Flagship, and similar strategic programs in China, the UK, and other nations, have played a crucial role in providing sustained funding and coordinating research efforts. These programs recognize the potential for quantum technologies to confer significant economic advantages and national security benefits, thereby incentivizing investment in a field with inherently long development timelines and high capital requirements. This strategic confluence of public and private investment has fostered an environment conducive to both fundamental breakthroughs and accelerated engineering development.

A Panoramic View of Quantum Hardware Architectures

The study provides an invaluable comparative analysis of six prominent quantum hardware platforms, each with its unique advantages, disadvantages, and specific suitability for different applications. These platforms represent the forefront of current research and development in quantum information science:

- Superconducting Qubits: Based on superconducting circuits that exhibit quantum properties at extremely low temperatures, these are currently at the forefront of quantum computing demonstrations, with several companies deploying them via cloud platforms.

- Trapped Ions: Utilizing individually trapped atomic ions whose electronic states serve as qubits, these systems boast high coherence times and excellent gate fidelities, making them strong candidates for universal quantum computation.

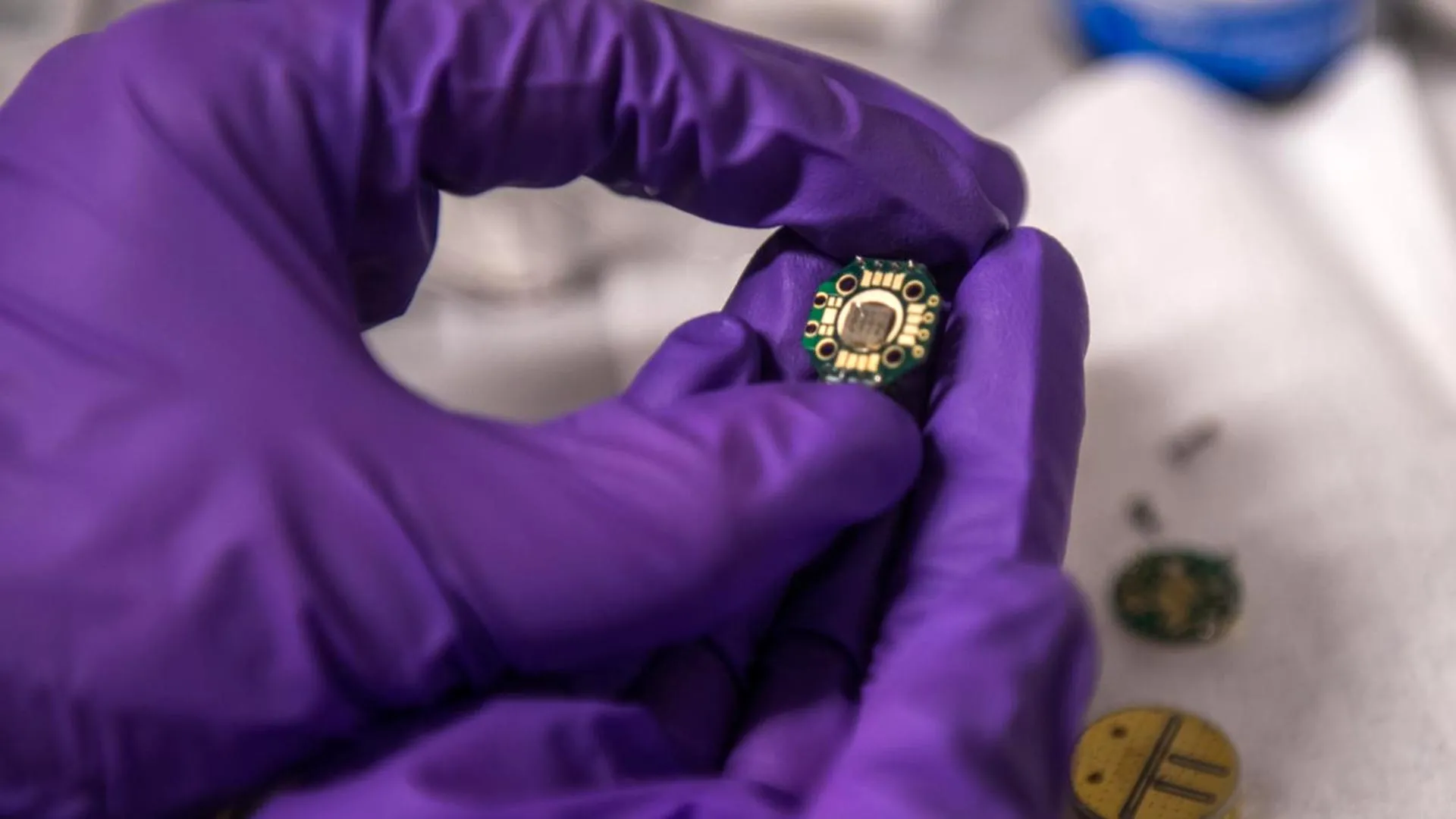

- Spin Defects (e.g., NV Centers): Often found in solid-state materials like diamond (nitrogen-vacancy centers), these defects possess electron spins that can be manipulated and read out, offering potential for robust quantum sensing and even distributed quantum networking, sometimes at room temperature.

- Semiconductor Quantum Dots: Tiny nanocrystals that confine electrons, acting as artificial atoms. Their potential for scalability and compatibility with existing semiconductor manufacturing techniques makes them attractive for future quantum processors.

- Neutral Atoms: Arrays of individual neutral atoms, typically manipulated by lasers, can be precisely positioned and entangled. These platforms are showing immense promise for quantum simulation due to their tunable interactions and potential for large qubit counts.

- Optical Photonic Qubits: Encoding quantum information in photons (particles of light), these systems are inherently fast and well-suited for long-distance quantum communication and networking, as photons are less susceptible to environmental decoherence during transmission.

To gauge the relative maturity of these diverse platforms across four key application areas—computing, simulation, networking, and sensing—the researchers employed an innovative methodology. They leveraged large language artificial intelligence models, such as ChatGPT and Gemini, to assist in estimating the Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) for each platform. TRLs, a standardized metric originally developed by NASA, range from 1 (basic principles observed in a laboratory environment) to 9 (technology proven in an operational environment). While the use of AI in this context is novel and offers the advantage of rapid, broad-spectrum data synthesis, it also introduces considerations regarding potential biases in the training data or interpretative nuances that might require expert oversight.

The analysis revealed a nuanced landscape. Superconducting qubits, for instance, scored highest for quantum computing applications, reflecting their current lead in developing programmable quantum processors. Neutral atoms demonstrated superior readiness for quantum simulation, owing to their ability to create large, controllable arrays of interacting qubits. Photonic qubits exhibited the highest TRL for quantum networking, leveraging light’s natural suitability for information transmission. Finally, spin defects emerged as the leader in quantum sensing, attributable to their inherent sensitivity to magnetic fields and other physical phenomena.

The Nuance of Readiness: Beyond Numerical Scores

It is imperative to contextualize these TRL scores. A higher TRL, while indicating more complete system functionality and development, does not automatically equate to imminent widespread commercial deployment or the cessation of fundamental scientific inquiry. William D. Oliver, a coauthor and the Henry Ellis Warren (1894) Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Professor of Physics, and Director of the Center for Quantum Engineering at MIT, offered a crucial historical perspective. He noted that early semiconductor chips in the 1970s, despite achieving TRL-9 for their time, possessed capabilities vastly inferior to today’s sophisticated integrated circuits.

Oliver emphasized that a high TRL for current quantum technologies signifies a significant, yet inherently modest, system-level demonstration. It does not imply that the scientific frontier has been fully explored or that only engineering refinement remains. Rather, it underscores that while substantial progress has been made, these systems still require considerable improvement and scaling to realize their full, transformative promise. The journey from a working prototype to a robust, commercially viable technology is often protracted, demanding continuous innovation across multiple disciplines.

Navigating the Labyrinth of Scaling Challenges

The path to utility-scale quantum systems is fraught with significant engineering and scientific hurdles. The paper meticulously outlines several major challenges that must be addressed:

- Materials Science and Fabrication: Producing consistent, high-quality quantum devices requires unprecedented precision in materials science and fabrication techniques. Defects at the atomic scale can severely degrade qubit coherence and performance. Developing reliable, repeatable manufacturing processes at scale remains a profound challenge.

- Wiring and Signal Delivery (The Tyranny of Numbers): As quantum systems grow from tens to hundreds, and eventually to millions of qubits, the problem of individually controlling and reading out each qubit becomes intractable. Most current platforms rely on individual control lines, leading to an overwhelming "tyranny of numbers"—a problem faced by classical computer engineers in the 1960s before the advent of integrated circuits. Solutions will likely involve highly integrated control electronics, cryogenic components, and advanced multiplexing techniques.

- Environmental Control and Power Management: Many quantum platforms operate under extreme conditions, such as near absolute zero temperatures (milliKelvin ranges) or in ultra-high vacuum environments, requiring complex and energy-intensive refrigeration systems. Managing power delivery, dissipating heat, and maintaining stable operating conditions for large-scale quantum processors presents formidable engineering challenges.

- Automated Calibration and System-Level Coordination: Current quantum systems often require extensive manual calibration and tuning to achieve optimal performance. As systems become larger and more complex, automated calibration routines, intelligent control software, and robust system-level coordination mechanisms will be indispensable.

- Error Correction: Quantum information is inherently fragile and susceptible to noise. Building fault-tolerant quantum computers requires implementing quantum error correction codes, which demand a vast overhead—potentially thousands or millions of physical qubits to encode a single logical, error-free qubit. Developing architectures that can efficiently implement these codes is a monumental task.

Lessons from History and a Prudent Outlook

Drawing further parallels to the extensive development timeline of classical electronics, the authors emphasize that many transformative breakthroughs—such as advanced lithography techniques and novel transistor materials—took years, often decades, to migrate from basic research laboratories into industrial production and widespread commercial adoption. Quantum technology, they contend, is highly likely to follow a similar, multi-decade trajectory.

To navigate this complex journey successfully, the paper advocates for several strategic imperatives:

- Top-Down System Design: Moving beyond incremental component improvements, a holistic approach is needed, designing quantum systems from the application layer down to the physical hardware, ensuring that components are optimized for overall system performance and scalability.

- Open Scientific Collaboration: Fostering an environment of open exchange and collaboration across academia, government, and industry is crucial to prevent premature fragmentation of efforts, accelerate knowledge transfer, and establish common standards and best practices.

- Realistic Expectations and Sustained Investment: The authors caution against the pitfalls of exaggerated hype, which can lead to unrealistic expectations and subsequent disillusionment. They underscore the importance of tempering timeline expectations, recognizing that significant breakthroughs often require sustained, long-term investment and patience. The promise of quantum technology is immense, but its realization will be a marathon, not a sprint.

The profound implications of fully realized quantum technologies—ranging from revolutionary advancements in medicine and materials science to fundamentally new paradigms in artificial intelligence and cryptography—underscore the critical importance of this current "transistor moment." The collective efforts of scientists, engineers, policymakers, and investors in the coming years will determine the pace and scope of this unfolding technological revolution, shaping the contours of the 21st century’s technological landscape.